With the budget rapidly approaching, many are questioning whether the UK still has what it takes to compete in global markets increasingly dominated by developing nations such as China and India.

Why are emerging economies growing so rapidly?

Increased globalisation has inevitably aided in helping these economies develop and grow at a dramatic rate. Increased FDI (foreign direct investment) into their economies has helped to increase overall investment and grow capital stock (infrastructure needed to produce goods and services), helping drive economic output, decrease poverty and improve the quality of living.

Although a lot of assumptions must be made when modelling GDP growth in this way, data and numbers behind economic modelling like this back up what we’re observing in these economies.

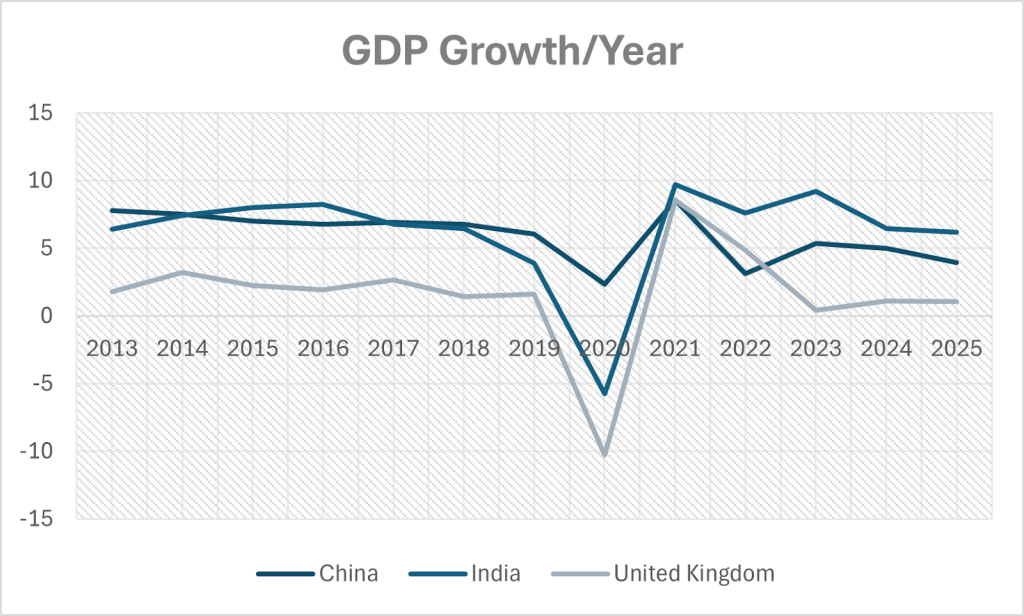

Source: IMF Real GDP Growth rate (%) 2013-2025

The post-pandemic boom

Post-pandemic, the UK was put in a similar position to developing economies like India and China, which can be seen in the data. In this sense the UK underwent a period of rapid GDP growth as human capital* returned to work and output rapidly increased as businesses resumed usual activity.

But as expected, the economy then slumped shortly after as diminishing returns** haunted the UK economy once again as the economy returned to normal rates of economic growth.

The challenge for developed countries

In developed economies like the UK, it is always going to be hard to keep up with the huge rates of growth observed in these countries.

The UK’s economy has already peaked and the depreciation of capital stock*** has caught up with our rate of investment and so we’ve entered a period of stagnation.

Options for the Chancellor

The Chancellor has a number of options for the budget, notably:

- Cut taxes on business and attract private sector investment.

- Increase taxation and increase public investment with the revenue.

- Increase public investment through government borrowing.

Realistically in this budget, the Chancellor is likely to avoid option one and three and focus on option two as she has suggested to the media that some tax rises may be coming and insisted that government spending will be decreased in the November budget.

Increasing public investment through borrowing would be contradictory in a budget which seemingly seeks to ‘balance the books’ through policies of fiscal responsibility and a perceived ambition to cut the deficit and reduce net borrowing.

Can the British economy improve?

Although the British economy does have room for improvement, the likelihood that the economy will uplift post-budget to any significant level is unlikely as the UK economy is nearing the steady-state, allowing for some negligible levels of economic growth, compared to other developing economies that is.

To grow, the UK needs one simple factor. Innovation. It needs to innovate and commercialise that innovation to drive new economic growth from technological progress – else we risk falling behind our G7 partners. We can no longer rely on increasing capital and production alone.

Defintions

* Human capital refers to the skills, knowledge and experience people bring to the workforce.

** Diminishing returns occur when adding more resources, such as labour or investment, produces smaller and smaller increases in output over time

*** Depreciation of capital stock means the gradual wearing out or ageing of a country’s physical assets, such as machinery, buildings and infrastructure, which reduces their ability to produce goods and services over time.