Chancellor Rachel Reeves has some tough decisions to make ahead of the next budget. Yet talk of tax increases on businesses and working people raises serious concerns. Can this budget truly deliver the growth and meaningful reform that the economy needs?

Regrettably, that seems unlikely.

Let’s be clear, government spending remains elevated, the deficit is persistent, and the need to sustain funding for public services is real. But tax increases are a short-term expedient that often stifles long-term growth. The UK has fallen into this trap repeatedly: rising taxes, slowing growth, and further fiscal pressure in a self-reinforcing cycle that weakens the economy over time. What is required now is vision, ambition, and a commitment to long-term economic health.

Harm to productivity

While taxation plays a vital role in funding essential services, excessive or poorly targeted taxes can dampen productivity by reducing incentives to work, save, and invest. If the goal is to stimulate private sector expansion, diminishing disposable capital through higher taxation is not the path to take.

History offers examples of the growth potential unlocked by supply-side reforms. The Reagan administration’s Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 dramatically reduced marginal tax rates, seeking to incentivise production and enterprise. This contributed to a period of widespread, robust economic growth.

Demand and output

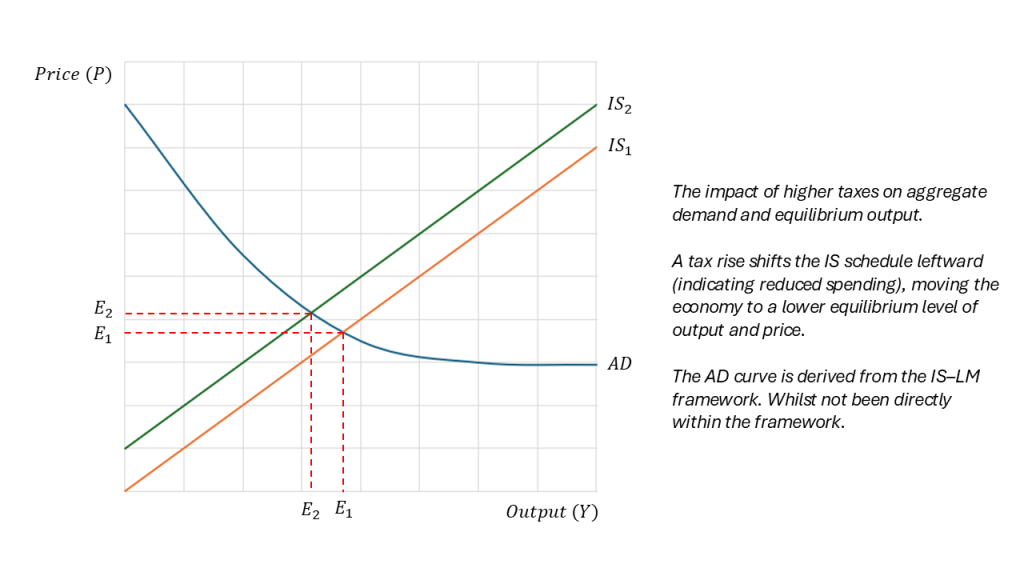

Economically, higher taxes reduce disposable income and weaken consumption. Within the standard IS-LM framework, this is represented by a leftward shift of the IS curve, leading to a lower equilibrium level of output and income in the short run. Put simply, consumers spend less, firms sell less, and economic activity slows.

In the present climate of fragile consumer confidence and weak retail performance, the timing of tax rises would be particularly damaging. While these effects are short-term, the broader consequences, slower investment and declining business confidence can persist well beyond the immediate adjustment period, restraining long-run growth potential.

A competitive world

Even if higher taxation were manageable in a closed economy, it poses greater risks in a globalised one. Increases in corporate or capital taxes can deter foreign direct investment (FDI), drive firms to relocate, and erode competitiveness.

Ireland’s experience illustrates how a low, stable tax regime can attract international business and transform economic prospects. By contrast, economies with consistently high corporate tax burdens, such as France, have struggled to sustain private sector dynamism. Of course, taxation is not the sole determinant of growth. Factors such as labour market flexibility, education, and infrastructure matter too, but fiscal competitiveness remains an essential part of the equation.

Fiscal responsibility

Raising taxes does increase government revenue in the short run, but only up to a point. The Laffer Curve illustrates that beyond certain thresholds, higher rates discourage economic activity and can ultimately reduce total receipts. While the UK is not currently at that limit, continued reliance on tax hikes to fill fiscal gaps risks moving us closer to it. Evidence already shows an expansion of tax avoidance and the use of efficiency schemes as individuals and firms adjust their behaviour to an increasingly burdensome system.

True fiscal responsibility is not simply about balancing today’s books; it is about creating the conditions for sustainable prosperity. An economy that punishes enterprise or deters investment in pursuit of short-term revenue undermines its own fiscal base. Growth is not the enemy of responsibility; it is the foundation of it.

Policy implications

Reeves appears determined to proceed with the government’s fiscal plan, and the political pressure to raise revenue is undeniable. Yet increasing taxes, especially on income and business, would be a step backwards. A policy framework that supports innovation, private investment, and competitiveness will generate stronger revenues over time without stifling productivity or morale.

Fiscal responsibility cannot be defined solely by restraint; it must also include foresight. The government’s commitment should be to leave the next generation an economy that works for them: dynamic, competitive, and confident in its ability to grow. Penalising enterprise and equating success with greed risks entrenching stagnation rather than overcoming it.

The choice is therefore not merely between spending and saving, but between short-term expedience and long-term stability. Reeves can choose to pursue growth through discipline and strategic reform, or she can risk placing the economy on a precarious path for years to come. The warning is clear: without a vision for sustainable growth, no budget can truly deliver prosperity.