Donald Trump’s foreign affairs approach is unique among US presidents – has he changed international relations for good?

Since the end of the Second World War, Western nations have largely backed down from what is known in international relations as realism, instead opting for increased globalisation and cooperation through intergovernmental organisations such as the UN.

This is often called the LIO or Liberal International Order. Historically, no countries subscribed to this concept more than the US, the UK and other nations in the anglosphere and wider Western world.

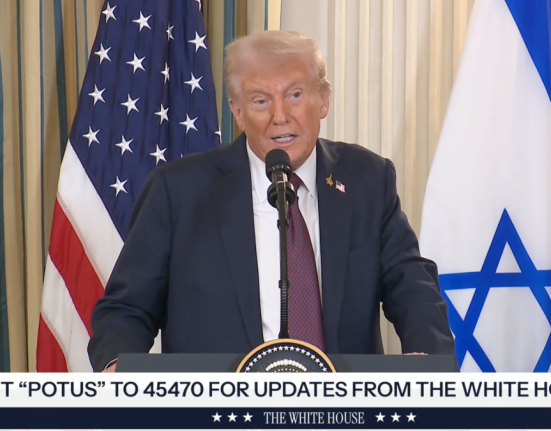

But that has changed. And it’s all down to one man: Donald Trump.

What is the usual?

Following the formation of the United Nations after the Second World War, many nations opted for increased global cooperation, democracy and a strong emphasis on respecting international law.

While rogue states such as North Korea and the Soviet Union, which later became Russia, failed to abide by the developing series of new international laws, conventions and governance, most countries began to look past imperialism and global domination, instead focusing on peace and international security.

Russia’s realist approach to international relations has long presented itself as an issue for Western nations as they try to leverage international law and intergovernmental organisations such as the UN against rogue states like Russia, China, North Korea, and Taliban-led Afghanistan, amongst other nations. But despite many attempts to retain international order through these organisations, these states have failed to listen and failed to abide by the laws other nations subject themselves to, begging the questions: What’s the point?

Many argue that this system does not work. Trump has said as much, which explains why he has shaken up US foreign policy since returning to the Oval Office.

Reasons for the breakdown

Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, Chinese aggression in the South China Sea and Iran’s harbouring of terror cells has led to a breakdown in trust within organisations such as the UN. Rogue states seem to be able to get away with breaking international law, whilst citizens in nations which bind themselves to such laws find themselves struggling to tackle complex issues of domestic policy due to legislation bound to them by the international laws.

Nations such as Russia, China, Iran and more have become so used to breaking international law that they have developed ways to circumvent sanctions set out to enforce it. Meanwhile, international bodies such as the EU appear weak and radiate an energy of ‘all words and no action’ as MEPs vote to condemn actions by malicious nations as opposed to backing real action to maintain international order. Put simply: criminals commit heinous crimes, and the states which are supposed to police them merely wag their fingers.

Where Trump comes into all this

From Trump’s perspective, the US has become weaker as it has followed international laws and conventions, whilst rogue states that have ignored these conventions are perceived to have become stronger. For example, Russia’s success in Crimea and the relative success so far in its invasion of Ukraine.

So what does Trump do? He reignites the US’ interventionist stance, launching tough military action against Venezuela, seizes a ship flying a Russian flag, and threatens Columbia, Mexico and Greenland with military action if he doesn’t get his way. And to an extent – it works.

America’s closest ally, the UK, seemingly backs some of the action, providing assistance in the seizure of the Bella-1 vessel in the Atlantic ocean through its surveillance support and the granting of permission to the US to use a Scottish airport to help seize the vessel.

But there is one key distinction. Whilst the US operation in Venezuela may have broken international law, the UK’s support of the US mission aboard the Bella-1 ship was branded by the UK as a ‘sanction busting’ mission and vitally aligns with international law as the action of the vessel to change its flag and affiliation put the ship in a legal dilemma whereby any state could have reasonably captured it and remained on the correct side of the law.

Although Trump’s actions in Venezuela have been subject to great deals of controversy, the move did undoubtedly serve one purpose, and that was to prove its military might. Whilst Russian troops struggle on the ground in Ukraine and their aircraft struggle to maintain air superiority, the US managed to suppress Venezuela’s air defences, much of which are of Russian origin, and capture the nation’s leader, all in just three hours. The operation served as a reminder to rogue political actors across the world that the US retains its supremacy in the field of conventional warfare.

Will this strategy work elsewhere?

It could be easily argued that Trump and the US got lucky on this occasion, but that was not the case. America’s relative success regarding its interventions in Syria and Iran proves that the US does still dominate militarily in a variety of settings. It’s this show of power which realist policy-makers like Trump leverage to get their way. It works because not only does it force people into subordination, but it also encourages peace through fear, whether that be rightly or wrongly.

Now Trump has Greenland in his sights. The US president has made it clear that he will do anything it takes to seize control of the NATO member’s territory. But with apparent universal condemnation by NATO members, support for such a move from typical allies makes the peaceful, democratic and legal seizure of the territory near impossible for Trump. The question as to whether he has the guts to use military force against a fellow NATO member is a difficult one to answer. Mainly because Trump’s foreign policy is one not only executed through strength, but also through ambiguity.

In Trump’s last term, following threats from North Korea, Trump retaliated through discourse by announcing he had a ‘big red button’ and ‘his works’. This not-so-straightforward threat positions the US in a way which emphasises strength whilst falling short of revealing how it would use that strength or whether it even would use it. Lo and behold, Trump became the first US president to cross into North Korea for decades.

Does Trump’s strategy work?

Well, the question shouldn’t be whether or not Trump’s foreign policy strategy works, but rather the extent to which it is applicable when dealing with different countries. Whilst this realist approach clearly would not work for the US when dealing with law-abiding Western nations, it has proven itself to be more effective at tackling rogue states. The issue, however, lies in whether or not these states are rational enough to avoid escalation. Serious discourse followed by tough action changes the expectations of world leaders and makes each threat more viable.

Discourse regarding the use of more serious weaponry, whether that be nuclear or conventional, could rapidly turn into an escalation and spiral out of control if the wrong policy-makers in the wrong countries believe it. So though Trump’s approach may work for now, the US president is undoubtedly walking on a tightrope and holding on by a very fine thread. If that thread snaps or he makes one incorrect move, it could lead to catastrophe.