No more life-long immunosuppression for organ transplant patients

Arduous traditional treatment to be replaced by “natural” cellular therapy in “five to 10 years”

Liver, kidney, heart and lung transplant patients will soon no longer have to undergo lifelong, body-weakening immunosuppression treatments to artificially ensure their donated organs survive.

The transplant surgeries themselves could also become unnecessary within the next five to 10 years if progress continues to be made by University of Birmingham experts on new cellular therapy treatment.

The breakthrough promises to save millions of pounds for the NHS, which currently carries out 4,600 organ transplants a year at £80,000 to £100,000 each.

Until now, transplant patients have typically required lifelong immunosuppression treatment, either partially or completely, to ensure their donated organs are not rejected by the body.

This ongoing suppression of a person’s immune system, using powerful steroids or drugs like azathioprine, mycophenolate or tacrolimus, can lead to severe side-effects, including osteoporosis, hypertension, diabetes, kidney failure and risk of cancer, as well as a reduced resilience against everyday colds, flus and other bugs.

Using a patient’s own “good” cells to combat “bad” cells

Professor Ye Htun Oo, of the University of Birmingham, says a new, natural treatment method he is developing – using a patient’s own “good” cells to combat “bad” cells – will be available to patients in as little as five years.

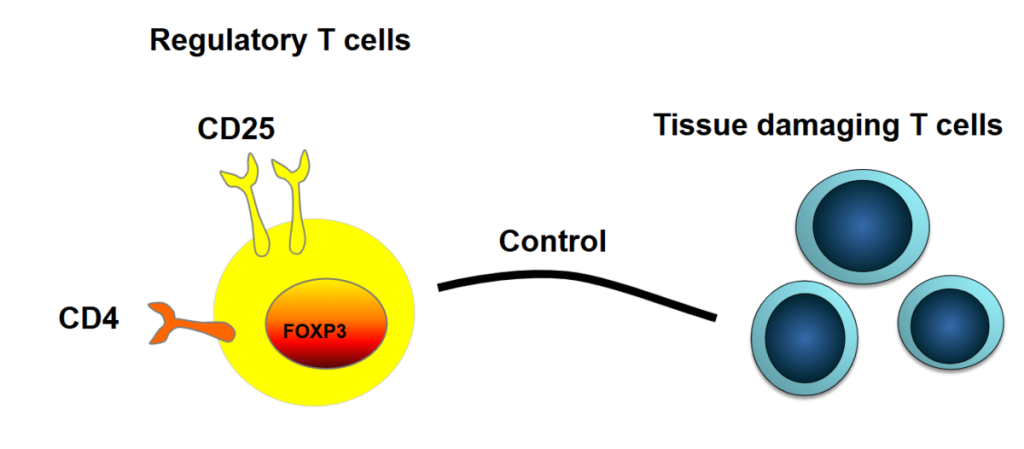

He and his team are advancing cellular therapy, where “regulatory T cells,” the body’s own natural defence force, are harvested from a patient, multiplied, made more effective and then loaded back in to defeat rogue cells that attack the body.

The new treatment will benefit organ transplant patients and people suffering from autoimmune diseases, including autoimmune liver diseases, Crohn’s, colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and pemphigus.

Prof Oo’s specialism is autoimmune liver diseases. Meanwhile, other teams of experts around the world are carrying out similar work to use regulatory T cells to treat other autoimmune diseases, with more than 200 clinical trials currently under way.

UoB team awarded £3.83m to progress research over next eight years

“In the next five to 10 years, regulatory T cell treatment will be available for autoimmune liver disease patients,” said Prof Oo, whose team was recently awarded £3.83m in funding from the Wellcome Trust.

“This new treatment we are developing uses the body’s own naturally occurring defence cells to defeat bad cells that mutate and start attacking the body. It’s natural and, in theory, simple.

“Until now, we have been able to help organ donor recipients and people with autoimmune diseases only through the use of steroids and other severe immunosuppressive treatments. But these treatments take a severe toll on the body, increasing the risks of horrible illnesses, not to mention weakening the body’s natural defence against everyday bugs.

Cellular therapy could remove need for organ transplants altogether

“Regulatory T cell therapy will save and prolong many lives. People may no longer need organ transplants at all, and if they do, they will no longer need lifelong immunosuppression treatments.

“This advance will also be a game-changer for people suffering with autoimmune illnesses such as autoimmune liver diseases, Crohn’s, colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and pemphigus.”

PHTA in Birmingham’s Life Sciences Quarter

Prof Oo plans to use the newly opened facilities in the Precision Health Technologies Accelerator (PHTS) on UoB’s Birmingham Health Innovation Campus (BHIC), part of the city’s fast-emerging Life Sciences Quarter, to carry out the translational work needed to bring cellular therapy to market.